On 5 January 2026, the Supreme Court (SC) ruled on bail pleas in the Delhi riots ‘larger conspiracy’ case. Five accused were granted bail. Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam were not. The SC made one point clear at the outset: bail under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) (UAPA) Act is not a judgment on guilt. It is a legal decision shaped by statute. The question before the SC was not whether the accused were innocent or guilty, but whether the law permitted their release at this stage.

The SC accepted that the case does not concern a ‘sudden riot’, but an alleged ‘planned conspiracy’ linked to the protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act in February 2020.

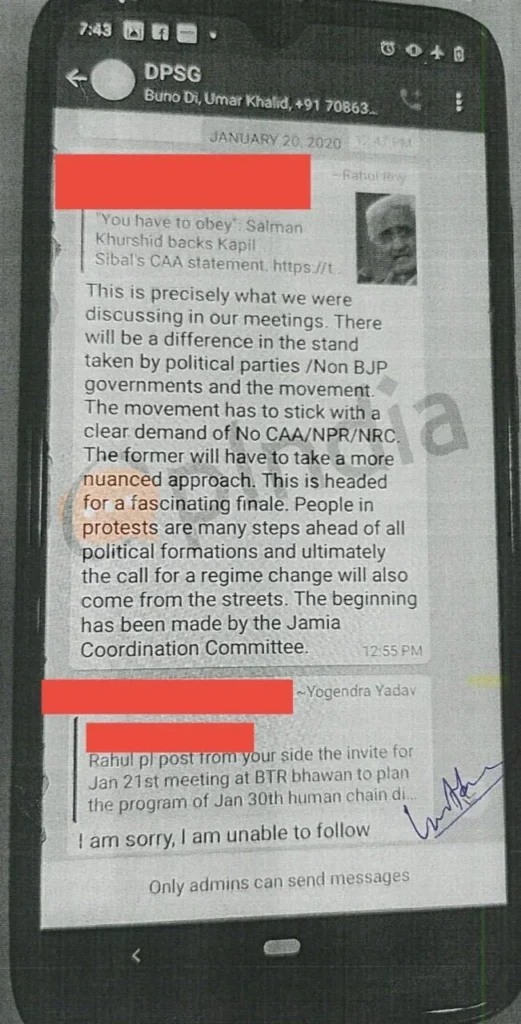

A conspiracy of ‘regime change’, which has been narrated in a WhatsApp message on a group called the Delhi Protest Support Group (DPSG), as reported by OpIndia. In the message, documentary filmmaker Rahul Roy wrote, ‘The movement has to stick with a clear demand of No CAA/NPR/NRC… ultimately, the call for regime change will also come from the streets.’ Other members of this group included Khalid and Yogendra Yadav.

At the bail stage, the prosecution’s version must be taken at face value, the SC said. According to that version, the violence led to 53 deaths, injuries to police personnel, and widespread damage, and was timed to coincide with an international visit to draw global attention. The SC stressed that it was not testing the truth of these claims. That task belongs to the trial. As of now, rejecting the prosecution’s story as improbable was not legally permitted.

Khalid’s political background and activism were discussed only in a limited sense. The SC did not treat dissent or protest as a crime. Nor did it suggest that political belief is unlawful. What mattered, in the SC’s view, was the prosecution’s claim that Khalid’s ‘influence’ and ‘organisational role’ were used to coordinate and mobilise others as part of a ‘larger plan’. Speech and meetings were examined not as expressions of opinion, but as alleged steps in a conspiracy. This distinction formed the backbone of the SC’s reasoning.

The central legal barrier to bail was Section 43D(5) of the UAPA. This provision sharply restricts bail if the accusations appear ‘prima facie true’.

Relying on earlier rulings, especially NIA vs Zahoor Ahmad Shah Watali, the SC reiterated that judges cannot examine contradictions, assess credibility, or consider the defence version at this stage. If the charge-sheet discloses a basic legal case, the SC’s discretion is narrow.

Applying this standard, the SC divided the accused into two categories. Khalid and Imam were placed in the category of alleged ‘central’ and ‘directive actors’—those accused of ‘planning, coordinating, and shaping events’. Physical presence at the riot sites, the SC said, is not necessary for conspiratorial liability. Others were seen as having ‘limited’ or ‘local roles’ and were therefore granted bail. The SC rejected the argument of parity, holding that bail depends on role, not numbers.

The argument of long detention was considered but rejected. Khalid has been in custody for over four years, with the trial yet to begin. On this, the SC held that delay alone cannot override the UAPA’s statutory bar. Citing KA Najeeb vs Union of India, it said that ‘only extreme’ and ‘state-caused delay’ could justify bail under such laws. That threshold, in the SC’s view, was not met. The same reasoning applied to Imam.

According to the Special Public Prosecutor Amit Prasad, seven of the fourteen adjournments in 2023–24 have been requested by Khalid’s side.

The judgment draws a narrow line between protected expression and conduct alleged to advance an unlawful conspiracy.

Although the SC confined its ruling to legal questions of conspiracy and bail, its implications were immediately felt in campus politics. At Jawaharlal Nehru University, some 30-35 students affiliated with Left student organisations raised slogans such as ‘Modi-Shah ki qabr khudegi JNU ki dharti par,’ highlighting a response focused on politics rather than the SC’s legal reasoning.

The SC’s January 2026 ruling makes it clear that intention is rarely read in isolation. The SC accepted that a long history of political mobilisation, when alleged to be followed by planning, coordination, and strategic direction, can give shape to a prima facie case of conspiracy. Where the allegations suggest continuity between past methods and present intent, the law under the UAPA demands caution, not release. Khalid’s continued detention does not reflect political animus, but the SC’s conclusion that alleged planning outweighs the claim to pre-trial liberty—at least until the trial itself supplies a final answer.

Nancy Mahavir Sharma is an LLM graduate who writes on law, policy, and judicial developments.